Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are an extremely common presentation to both primary and secondary care services. The term UTI encompasses a wide range of clinical conditions as a result of microbial pathogens in the urinary tract. This can involve the upper tract e.g. kidneys and ureters and the lower tract e.g. bladder and urethra They are more commonly known as pyelonephritis referring to infection in the renal pelvis and upper ureters and cystitis being infection in the bladder. Prostatitis whilst being a distinct entity is associated with UTI in other areas of the urinary tract and occurs in males when infection infiltrates the prostate. [1]

Epidemiology & Pathophysiology:

Around 1 in 3 women have had UTIs by the age of 24 and around half of all women report at least one UTI in their lifetime [2]. UTIs are less frequently seen in men of all ages but do occur and increase in prevalence with age. Females are more prone to UTI due to variation in the anatomy of the urological system including the shorter length of the urethra in females compared to males, allowing for easier ascending movement of pathogens up into the bladder and the relative closer proximity of the vagina and rectal areas.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are caused by inflammation of the urinary epithelium, with the most common cause being gut flora such as E.Coli which makes up a large majority of the culpable organisms that cause UTI [3] In general, uncomplicated lower UTIs involve the lower system of urethra and bladder. If there begins to be inflammation in the ureter and kidney then this becomes a higher UTI or acute pyelonephritis and is normally associated with patients who are more clinically unwell and often have more significant and systemic symptoms. It is important in the patient workup to establish if the patient has any evidence of these more complicated presentations such as acute pyelonephritis or if the patient is developing sepsis as the management is likely to differ considerably.

The process of UTI begins with an invading organism such as E.Coli ascending up the urethra in a retrograde direction and causing inflammation in the urethra and bladder. This inflammatory response triggers stretch receptors in the bladder resulting in the sensation of bladder fullness and a need to urinate. The irritation also causes pain resulting in the common UTI symptoms of suprapubic tenderness, dysuria, frequency and urgency. Haematuria can also occur in response to this inflammation, this is more often microscopic and detected on urine dipsticks as opposed to being seen visually or macroscopic.

If the infection ascends further up the urinary system resulting in acute pyelonephritis the symptoms of which include fever, flank pain without the aforementioned symptoms of lower UTI. Pathogens can invade the bloodstream and result in sepsis [4] [5]. A differential diagnosis should be considered in younger patients without temperatures (< 37.8c). This includes PID, cholecystitis or renal colic [6]

Risk Factors:

Elderly patients are worth special mention in that they can present with more complex UTIs and often with less well-localised symptoms. They may be afebrile or have low-grade fevers and verbalisation of symptoms may exist as a result of acute confusional states, pre-existing medical conditions, reduced levels of consciousness, lethargy/ malaise and generalised weakness.

Postmenopausal women are at increased risk of UTI as drop a in oestrogen = increase in vaginal pH = vaginal colonization of Enterobacteriaceae which can spread to the urethra causing infection. [7]

One of the most statistically accurate diagnostic indicators is the patient who has suffered a UTI previously who tells you they feel they have developed a UTI again (FIND REFERENCE)…

Dementia + Parkinsons patients are at risk of something called neurogenic bladder. Reduced communication of afferent nerve pathways means they hold onto urine for longer, as they don’t receive the sensation of bladder fullness. [8]

Patients who have a catheter have an increased risk of developing a UTI as it represents a vessel to intrain and harbour bacteria.

History Taking, Assessment, Pertinent findings and What is not a pertinent finding:

Enquire about lower abdominal discomfort and explore this with SOCRATES, ask about flank pain, systemic symptoms of fever, nausea, vomiting, malaise, rigours and confusion, along with screening for the symptoms suggestive of sepsis.

Ask around symptoms of cystitis suprapubic pain, frequency, urgency, dysuria and enquire about blood seen in the urine.

A positive finding on Murphys punch / costovertebral angle tenderness. [10] may indicate a higher UTI and pyelonephritis.

Differentials

We should also conduct a specific review of systems to screen for other differentials so should ask around

Gynaecological infections e.g. PID – pelvic pain, vaginal discharge/ bleeding, Dyspareunia, menorrhagia, new or multiple sexual partners, unsafe sexual practices.

Prostatitis - symptoms the same as UTI + perineal/ penile/ rectal pain. Possibly retention of urine, difficulty voiding, lower back pain, pain on ejaculation, tender swollen/ warm prostate on DRE.

Other scrotal / Ovarian pathology – consider ovarian/ testicular torsion, ruptured ovarian cyst

Renal Colic – abrupt onset of unilateral flank/ loin to groin pain, significant pain +++, waxing/ waning and not able to find a position of comfort.

Appendicitis – Generalised umbilical abdominal pain that migrates to the right iliac fossa after several hours, fever, anorexia, vomiting, Mcburney’s point tenderness. Always keep malpresentation of appendicitis in mind. Due to its location and varied position it can cause irritation of the bladder and bowel and cause associated misleading symptoms.

Urological/ Gynaecological cancers – unexplained weight loss, night sweats, lower urinary tract symptoms often in older adults more commonly males. Unremitting and progressive back/ abdominal/ pelvic pain. Painless haematuria or vaginal bleeding especially in older adults. Always refer if concerned on a 2 week wait basis via the GP.

Confusion in the Elderly - This is a common presentation often associated with UTIs by clinicians, but we should be wary of just assuming confusion is caused by UTI. We can use the pneumonic PINCH ME to consider other causes.

Pain

other Infection

poor Nutrition

Constipation

poor Hydration

other Medication

Environment change

Various studies have linked UTIs with delirium but they all had major methodological flaws that likely led to a result bias. This means that it is exceptionally difficult to ascertain the degree to which UTIs cause delirium and this is definitely an area that needs more research.

“A negative urine dipstick DOES NOT exclude a diagnosis of UTI, especially in the presence of 2 or more symptoms of such.”

Tests: Urine dip, MSU and Ultrasound

Urine Dips - The Royal College of General Practitioners guidelines as well as CKS NICE both state that patients over the age of 65 should NOT have their urine dipped. The guidance is the same for those patients who have been catheterised.

By 80 years half of older adults in care, and most with a urinary catheter, will have bacteria present in the bladder/urine without an infection. This “asymptomatic bacteriuria” is not harmful, and although it causes a positive urine dipstick, antibiotics are not beneficial and may cause harm. [12] [13]

As a matter of course, however, pregnant women should receive a urine dip in an infection screen and if positive, even in the absence of symptoms, be referred for antibiotics.

Urine culture - (which is not the same as urine dipstick) is the gold standard diagnostic test for identifying UTIs. This involves collecting a mid-stream urine (MSU) sample and sending this off for microscopy, culture and sensitivity. Not only will this confirm the presence of infection and causative organism it can also provide guidance on antibiotic therapy indicating which antibiotics the causative organism is susceptible and resistant to [11]. As the attending clinician, we can collect samples on behalf of the GP and drop it off to allow targeted antibiotic therapy.

Renal ultrasound is another tool used in the diagnostic process of those who present with acute pyelonephritis. This can be done at the time of admission or delayed and done as follow up in a urology outpatient clinic. Its primary purpose is to check for complications including hydronephrosis and renal abscess or when there is concern surrounding an infective renal calculus. It is not a necessity on all patients with pyelonephritis, however. Those that have recovered well, without ongoing concerns do not necessarily require follow up. However, this can be left to the discretion of the primary care team/ GP who should be involved and closely monitor any patients managed in the community setting.

“Urine dips in the over 65s should NOT be performed as they give false positives”

Treatment:

The differentiation between cystitis and pyelonephritis is important in terms of resulting morbidity, choice of antibiotic and length of treatment.

Simple Cystitis can often be self-managed and may be appropriate for a watch and wait approach.

More complexed Cystitis, that hasn’t self resolved or is recurrent or progressive, Patients with a high risk of complications (Diabetics, immunocompromised, heavily comorbid, frail etc ), Males and pregnant patients should be referred for antibiotics.

Pyelonephritis will most often require 7-10 day courses of antibiotics and an ultrasound which can be done acutely or after discharge. It is difficult to decide which patient with pyelonephritis should be admitted to hospital. However, NICE does provide some clarity on who and why admission is warranted;

Signs of sepsis including- Significant tachycardia, hypotension or breathlessness

Marked signs of illness (impaired conscious level, profuse diaphoresis, rigors, pallor or significantly weak and reduced mobility

Temperature lower than 36 degrees or high fever

Vomiting and not able to keep down fluids or medications.

Those with a high risk of complication such as

§ Diabetics

§ Immunocompromised

§ Renal disease

§ Significant co-morbidity

§ Pregnant Patients [9]

Be wary of subclinical pyelonephritis in diabetics or those with incomplete recovery after antibiotics. subclinical pyelonephritis where patients present with mainly cystitis symptoms and then present with more characteristic features of pyelonephritis and with treatment failure. This is well recognised in diabetics.

Cranberry Juice: - There is no evidence of use of cranberry juice is helpful [14]

Safety Netting:

As always we need to ensure our patients are safety-netted and warned of the signs and symptoms of deterioration. Ensure we have discussed the complications as covered above and we are explicit about when they should call back for advice. If we are deciding to watch and wait. We need to be clear when the patient should seek their GP’s advice for antibiotics and if possible alert the GP as to our plan.

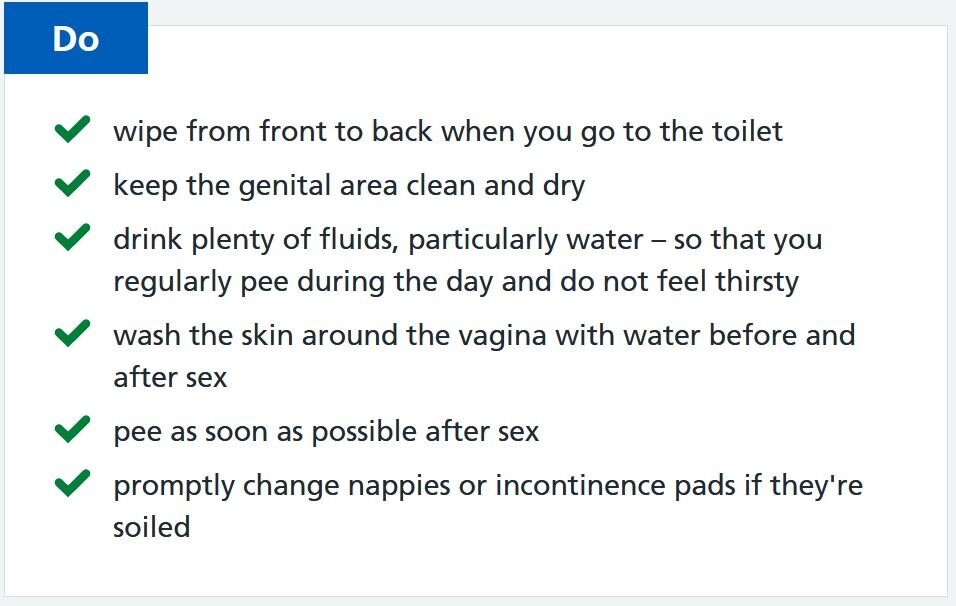

We can also give health promotion advice to help avoid recurrent UTIs(see right) . Reaffirm the importance of drinking lots of water, not holding onto urine and particularly for female patients urinating after sex, to minimise the risk of bacteria accumulation. [15]

Remember, clinicians are responsible for their own practice. These podcasts are produced for informational purposes and should not be considered solely sufficient to adjust practice. See "The Legal Bit" for more info.

If you’ve got any comments on the article please email generalbroadcastpodcast@outlook.com or post in the comments section.

Don’t forget to tweet and share GB if you like us using #FOAMed. If you like the podcast please leave us a review on the App store as it really helps boost our visibility, that means more people can find our CPD and we can keep making free open access paramedic education.

References:

1 -https://www.rcemlearning.co.uk/modules/urinary-tract-infections/lessons/definition-26/.

2- https://patient.info/doctor/urinary-tract-infection-in-adults

3- Norris DL 2nd, Young JD. Urinary tract infections: diagnosis and management in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008; 26(2): 413-30.

4- McCance, K. and Huether, S. (2019) Pathophysiology: the biological basis for disease in adults and children. Missouri. Elsevier.

5- Sepsis Trust UK 5th Edition Sepsis Manual (2019)

6 - Johnson JR. Acute Pyelonephritis in Adults. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:48-59.

7- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3246510/

8- https://www.belmarrahealth.com/neurogenic-bladder-elderly-causes-symptoms-treatment/

9 -https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/pyelonephritis-acute/management/management/

10 - https://infogalactic.com/info/Costovertebral_angle_tenderness)

11- https://labtestsonline.org.uk/tests/urine-culture

12 - Nicolle LE, Mayhew WJ, Bryan L. Prospective randomised comparison of therapy and no therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria in institutionalised elderly women. Am J Med. 1987 Jul; 83(1):27-33. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3300325

13 - Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2003;17(2):367-94. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.379.5055&rep=rep1&type=pdf

14 - Howell ABUpdated systematic review suggests that cranberry juice is not effective at preventing urinary tract infection evidence-Based Nursing 2013;16:113-114.

15- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-utis/